This is a really interesting path to go down, @joeylovestrand. I’m also struggling with how this could be implemented in a field methods class in any sort of meaningful way.

In a certain sense, a field methods course is a field methods course: students need a venue to learn how to do elicitation, practice how to interpret the responses of a consultant, appreciate the ambiguities and puzzles of linguistic data. All of these competencies are valid and important, and, in some ways, really enough on their own to occupy a class of students for a full semester.

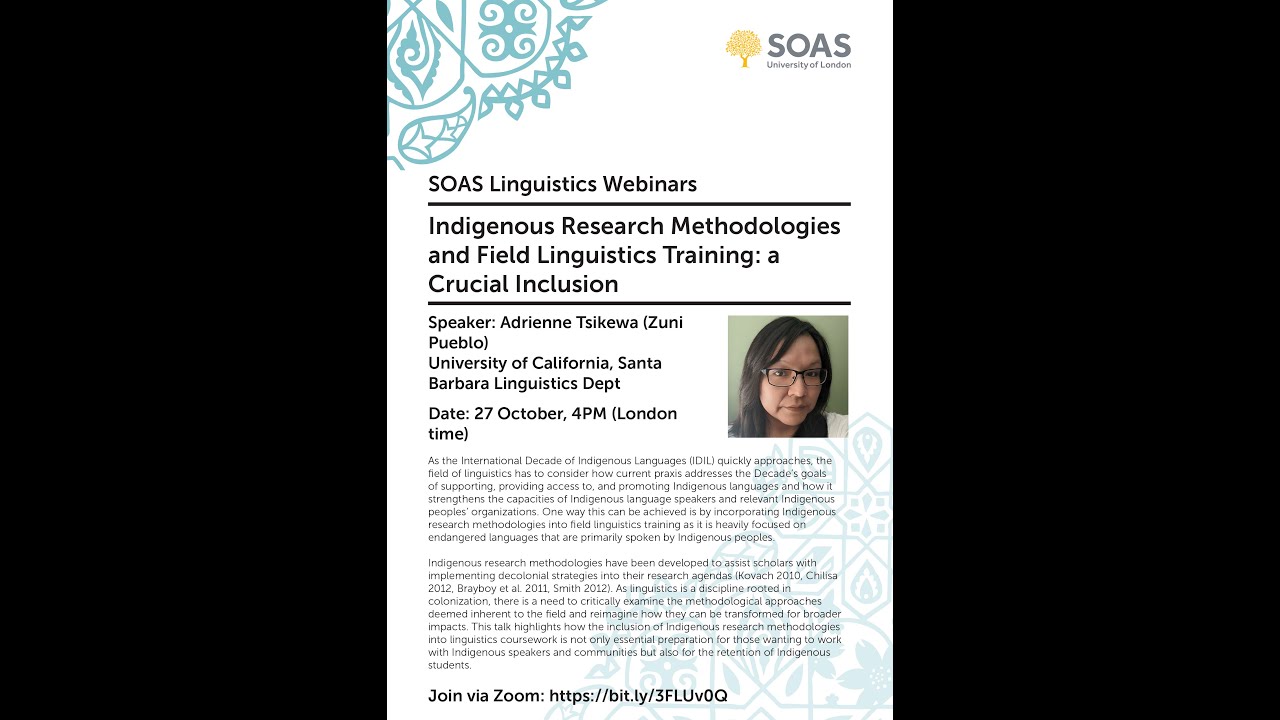

The other side of this coin is that the competencies highlighted in Tsikewa’s article are also crucial, and implementing them can’t simply be a case of adding a lecture or two, or pretending that a pre-elicitation talk with the consultant will, in any way, prepare students for the work of building long-term community relationships in a real-life field situation. In the same way that I think it’s not appropriate for a field methods class to try and assemble a sketch grammar of their target language in the space of a one semester field methods class, I also think it’d be just as inappropriate to expect a field methods class to engage with a speech community in any sort of meaningful way within the confines of one semester.

I once asked Friederike Lüpke about models of a field methods course which she saw as exciting. She told me that she was planning to conduct a field methods course not with a single speaker, but embed the course within a local diaspora community. I’ve thought about this approach ever since: instead of everything taking place within the classroom, and with one speaker, students would be expected to spend maybe half of their class time actually engaging with a community of speakers (understanding the social realities, learning about the challenges, finding speakers, recording consent, etc.). I feel like this would be ideal in a situation in which a linguistics department had already committed to a long-term relationship with said community (similar to SOAS linguistics’ relationship with the Sylheti community in London). In this way, students would gain first-hand experience working within a long-term project, but would also get a chance to practice things like elicitation, listening to speakers, working with linguistic data.

My final thoughts for the day have to do with accessibility: a linguist working in a real field situation should enter the project assuming that they will, in some way, be connected to the people with whom they work for the rest of their lives. This can take many forms - only some of which being a long-term linguistics project. But - should linguistics students (at least those who are just taking a field methods course) be held to the same standard? How do we make field methods (a course which I believe all linguistics students should take, no matter what subdiscipline they eventually settle into) as easy as possible for students to take, to enjoy, and, ultimately, to want to learn more about?