Digging a little deeper into HTML

Last time we learned that an HTML file is just a plain text file that is in a particular format — basically, HTML contains content <tag>wrapped up in “tags” like this</tag>. We also tried downloading an HTML file and editing it locally.

Did you try the exercise in the previous A Little Web? (Click here to let us know!)

- I tried and it worked.

- I tried, but I couldn’t get it to work. (Please feel free to ask for help on that topic!)

- I didn’t try.

- Please, like I have time for that.

0 voters

But what is HTML, anyway?

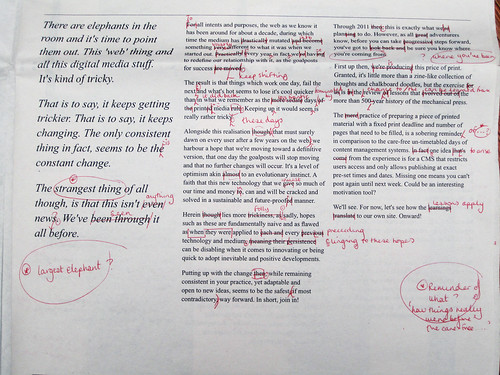

The ML in HTML stands for Markup Language (we’ll get to the HT later). “Markup”, in its oldest sense, means this kind of thing:

…you know, the kind of thing you suffer through in school, the old red pen. It’s sort of interesting to step back and ask, what do those red squiggles actually mean? In some cases, at least, they are circles around parts of the document — (the ones that should be fixed to make your instructor happy).

But in the HTML sense of “markup”, everything in a document gets “circled”. Every part of a document — every paragraph, every heading, every sidebar, everything — “marked up” as having a beginning and an ending. Since a text file (as we said before) is really just a series of characters, the only kind of “marking up” you can do is to say “now I’m about to start a part…” and then when you come to the end of the part, you say “I just finished that part I told you about before.”

Saying “here comes a part” and “there went that part” is basically what HTML tags are for.

Disregarding for the moment the rather weird and uniquely formatted <!doctype html> bit at the beginning of the file, the most fundamental tag in any HTML file is always (surprise!) <html>. You’ll notice that (aside from the aforementioned doctype thingy), an HTML file begins with <html> (the opening tag), and it ends with </html> (the closing tag). Anything between those two tags is said to be “inside” the <html> tag.

So, here’s a full HTML page for you to ponder:

<!doctype html>

<html>

<head>

<title>A few phrases in Esperanto</title>

<meta charset="UTF-8">

</head>

<body>

<p><strong>Mi amas vin.</strong></p>

<p><em>I love you.</em></p>

</body>

</html>

The indentation gives you some idea of the “nesting” of tags in this document: the <head> tag is “inside” the <html> tag, the <title> tag is inside the <head> tag, etc. Note that tags can contain either text and/or other tags. The text A few phrases in Esperanto is inside the <title> tag. (It is also a bit misleading since there is only one phrase in the document! Oh well.)

When your browser reads the HTML page, it reads through the tags in order, building up a “tree model” of the page as it goes. So, so far, we’ve “read” this far into our page:

<html>

What’s next? Whatever opening tags are right under our “top-level” (sometimes also called the “root”) tag. In our page, there are two: <head>, and then <body>. Note that we’re only one level deep at this point — <head> closes before the <body> tag opens. So the “second” level of depth in our document looks like this:

<html><head><body>

And we can keep going in this fashion. In fact, our simple little document is fairly deep — the <strong> tag that contains the actual Esperanto sentence Mi amas vin is four levels down.

<html><head><title>

<body><p><strong><em>

Okay, let’s enhance our documentation by adding morphological analysis. There are many ways that you might “mark up” the words of an interlinear gloss. The pattern of nested tags is in some respects more important than the particular tags you use. We’ll introduce three new tags here: <ol> for “ordered list” (a numbered list); <li> for “list item”; and <span> which is a very generic tag for marking up a bit of text (for whatever reason). Here’s how the source of our HTML document looks with those tags added:

<!doctype html>

<html>

<head>

<title>A few phrases in Esperanto</title>

<meta charset="UTF-8">

</head>

<body>

<p><strong>Mi amas vin.</strong></p>

<ol>

<li><span>mi</span> <span>1S</span></li>

<li><span>am-as</span> <span>love-PRES.IND</span></li>

<li><span>vi-n</span> <span>2S-ACC</span></li>

</ol>

<p><em>I love you.</em></p>

</body>

</html>

Note that we’ve embedded each form and gloss for each word in spans. That tells the browser that it should treat those “bits of text” as being “at” a particular level of nesting in the document.

If we look at that page in the browser, it will look like this (admittedly a bit hard to read!):

Default rendering [View page | HTML source]

In order to understand what is a structured document, and structured documents are great. If you pull back the curtain a little, you will see that there is a whole world of things that are possible with them. For just one tiny, obvious example, consider the difference between the previous presentation and the one below:

Styled rendering [View page | HTML source]

So what is the difference between those two? In terms of “how it looks”, you’ll notice that the second version looks much more like “real” linguistic notation. This is because we have provided the browser with some guidance about how we want the “parts” of the page to be presented: namely, each word is represented with a form and a gloss which are presented vertically with respect to each other, and which wrap as a unit. That is, the form/gloss pair that represents the work wraps just as if it were a single word. That’s how things work in documentary notation, and that’s how we want our interlinear sentence to behave. Note that in order to force the wrapping (the sentece only has three words!), we have squeezed the sentence into a skinny box.

If the box is less skinny, there is no wrapping (this is actually the very same content as the previous demo)

Control of layout like this is done with another language called CSS (Cascading Style Sheets). That’s a whole ’nother topic, but because wrapping glosses like this is so fundamental in web documentation, I’ll just show you how this was done:

ol {

display: flex;

flex-wrap: wrap;

}

li {

display: grid;

margin-right: 2em;

}

li span:first-of-type {

font-weight: bold;

}

We’re not going to go into how that works right now because it’s a bit fancy-pants. Suffice it to say that CSS like this can be added to a web page by inserting it inside a <style> tag. If you take a look at the source links for the second example above, you’ll see those rules inside such a tag. (There is more than one way to achieve this same effect with CSS, by the way. That’s not a bad thing.)

But I hope it’s clear that it doesn’t take much CSS to create an interlinear gloss with reasonable behavior. Note that because this wrapping works, the same content could be viewed on different devices (a phone, a tablet, a desktop computer) and still render correctly.

That flexibility in rendering is only possible because HTML documents are “structured” — they encode the fact that the form and the gloss are “in” a word, as it were. PDFs certainly don’t do this, and it’s well-nigh impossible to do in a word processing document.