We are all familiar with the problem of “legacy” documentation: important materials which are pre-digital, and thus have not made the leap into the digital era. It takes a ton of work to do such digitization — up to and including re-typing entire works.

But what about materials that were published to the web, only for those sites to go dark? That phenomenon is doubly sad, since not only is the content no longer available, it’s digital content that’s being removed.

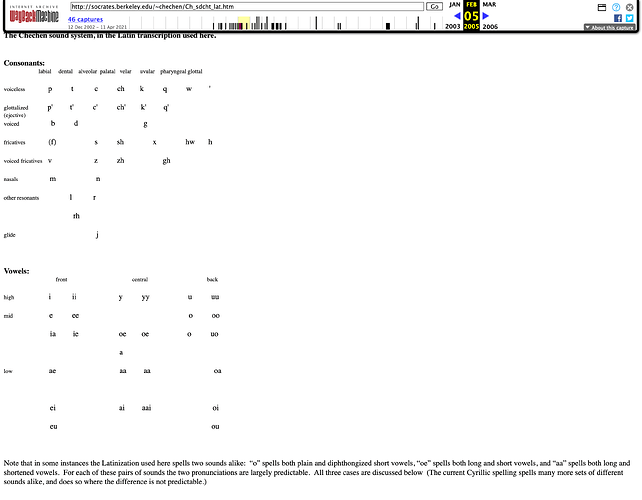

I happen to have been poking around in materials about Nakh-Daghestanian lately (as one does, for no particular reason), and somehow ended up on a page about Chechen. Except, it’s not actually there. Here’s the link:

http://socrates.berkeley.edu/~chechen/Ch_sdcht_lat.htm

And we get this:

Everything was essentially deleted from Berkeley’s servers in 2018.

Well, the site is still available in the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine, here:

https://web.archive.org/web/*/http://socrates.berkeley.edu/~chechen/Ch_sdcht_lat.htm

Servers are volatile

Here’s the thing. We’re talking about Berkeley here. This is not an institution which doesn’t have resources. If that university is going to let its content fade away, then we should suspect that any institution’s content is subject to fading away.

The problem can be even worse for languages with very limited resources online. Consider Beja, a Cushitic language (hi @Sosal!) which is of great typological interest. All of the external references from the Wikipedia article about the language are links to archived versions available only in the Internet Archive:

- Sakanab - Bidhawyet

https://web.archive.org/web/20090414041240/http://www.sakanab.co.uk/bidhawyet.htm - Klaus Wedekind - Linguistics

Klaus Wedekind - Linguistics : INDEX-Page - “Beja cultural research association”.

https://web.archive.org/web/20110725053758/http://bejaculture.org/CONSTITUTION.html

This is not the internet we want. The Internet Archive is a wonderful thing and all (I donate every year), but there should not be a single point of failure for language documentation.

What’s the solution?

What do you think? How do we combat this problem? And how do we protect new documentation on the web? After all, it is not impossible that one of the important archives that we rely on in linguistics could lose funding, heaven forfend. What happens then?

I can think of a few strategies, at least:

Publish to multiple places on the web.

Don’t just put your content in an archive. Put it in an archive, and elsewhere. This could be a domain you manage yourself, or GitHub pages, or… I don’t know, maybe more than one archive? This is probably a bad idea. See @JROSESLA’s comment below.

Make licensing status clear

Publish documentation with a clear documentation how the content can be reused. If you want your work to be spread far and wide, then say so. https://creativecommons.org/ might be a good option for specifying how content can be reused.

Publish machine-readable versions of the data as well as human-readable versions.

PDFs look nice, but they are hard to parse, search, and reformat. A data file like .csv, .xml, or .json is comparatively easy to do those things with. By publishing both instantiations of documentation, the data is more future-proof.